David Wojnarowicz

Biography

David Wojnarowicz channeled a vast accumulation of raw images, sounds, memories, and lived experiences into a powerful voice that was an indelible presence in the New York City downtown art scene of the 1970s and 80s. Through writing, film, painting, drawing, photography, mixed-media installations, and performance, Wojnarowicz affirmed art's vivifying power in a society he viewed as alienating and corrosive, especially for those who were not part of the “pre-invented existence” of the mainstream. Using blunt symbology and graphic illustrations, he exposed what he felt this mainstream repressed: poverty, abuses of power, blind nationalism, greed, gay sex, and the devastation of the AIDS epidemic. His nihilism, however, was also infused with his celebration and empathetic documentation of the alternative histories that he witnessed and lived.

Born in Red Bank, New Jersey in 1954, Wojnarowicz left an abusive home at a very young age. Though he was nomadic and traveled widely, from the 1960s on New York City was his primary home and landscape, where his sexual and artistic identity was both formed and expressed. An early representation of this is Rimbaud in New York (1978-79), a series of twenty-four black and white gelatin silver prints, showing men (either Wojnarowicz or surrogates for him) wearing face masks of the 19th-century French symbolist poet as they posed in contemporary gritty urban settings. The series was published in the Soho Weekly News and was the first official showing of his art.

In the early 1980s, Wojnarowicz was leaving his own set of symbols throughout the city, in the form of street graffiti, flyers for his band 3 Teens Kill 4, action installations such as Hunger, made in collaboration with Julie Hair (for which he dumped a heap of bloody animal bones in Leo Castelli’s stairwell), or in shows at such legendary East Village venues as Civilian Warfare, Club 57, and Gracie Mansion Gallery. In 1985 he was included in the Whitney Biennial with the large collage Science Lesson (1981-82), which depicted burning figures and the detritus of "Western Civilization" floating like junk in the gravity-less wasteland of the moon. Contextualized in a gallery with works by Jack Goldstein, Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Dara Birnbaum, and Barbara Kruger, Wojnarowicz’s visual strategies bore comparison with those of the so-called Picture Generation artists, in particular their ironic use of appropriated mass-media iconography to decry consumerism and cultural homogenization.

The art historian John Carlin draws out Wojnarowicz’s departure from the cool conceptualism often associated with this group by comparing him to Walt Whitman: "Wojnarowicz’s work is a modern Song of Myself--forging a new American idiom from personal history and contemporary culture. Whereas Whitman's work made verbal poetry from the rhythms of New York slang and the rhetoric of American journalism, Wojnarowicz's work is a form of visual poetry which emerges from popular culture, social history and his own dreams and visions." This characterization is reflected in Wojnarowicz’s own description of the symbiosis of experience, memory, history, dreams, and emotion. In his essay In the Shadow of the American Dream, Soon All This Will Be Picturesque Ruins, he writes: “There is really no difference between memory and sight, fantasy and actual vision. Vision is made of subtle fragmented movements of the eye. These fragmented pieces of the world are turned and pressed into memory before they can register in the brain. Fantasized images are actually made up of millions of disjointed observations collected and collated into the forms and textures of thought.”

The collapse of recorded and recalled experiences with dreamlike imagery--often structured around primal dichotomies of humanity and nature, the past and present, the powerful and powerless, the sensual and the austere--is an aspect of Wojnarowicz’s process as an artist across all media. His unique vocabulary of recurring themes and symbols connects his work as a writer, filmmaker, photographer, painter, and activist.

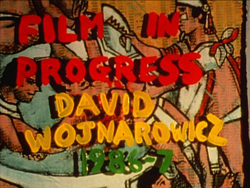

A significant example of this is his unfinished film A Fire in My Belly (1986-87), comprised of super-8 film footage shot on a trip to Mexico, integrated with staged scenes of imagery that also appears in his paintings and photographs, including locomotives and gears to represent industrialization, religious souvenirs to represent belief systems, and fire to represent the force of nature.

Wojnarowicz’s vocal position against censorship of any kind is a major aspect of his art, drawn from his own struggles identifying as a gay man in a conservative political climate, but also generalized to an awareness of the totality of a repressive society and its denial of eroticism, mortality, and individualism. This can be seen in the subject matter of his artwork and writings, his association with Cinema of Transgression figures such as Richard Kern and Tommy Turner, and also in his willingness to publicly resist censorship.

Postcards From America: X-Rays From Hell, which was written for Nan Goldin's AIDS-themed exhibition at Artists Space in 1989 after the AIDS-related death of Wojnarowicz’s mentor Peter Hujar and Wojnarowicz’s own diagnosis with the disease, expresses a powerful drive to make public art in the face of the power structures he had protested throughout his career--though in this case he explicitly implicates the political lingo of the time: “To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific repercussions in the pre-invented world ... Each public disclosure of a private reality becomes something of a magnet that can attract others with a similar frame of reference; thus each public disclosure of a fragment of private reality serves as a dismantling tool against the illusion of ONE TRIBE NATION; it lifts the curtains for a brief peek and reveals the possible existence of literally millions of tribes, the term GENERAL PUBLIC disintegrates, what happens next is the possibility of an X-RAY OF CIVILIZATION, an examination of its foundations. To turn our private grief at the loss of friends, family, lovers and strangers into something public would serve as another powerful dismantling tool. It would dispel the notion that this virus has a sexual orientation or a moral code or the notion that the government and medical community has done very much to ease the spread or advancement of this disease.”

Wojnarowicz died of AIDS-related illness in 1992. In 1999, Dan Cameron organized a major exhibition of his work for the New Museum, entitled Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz. Published collections of his writing include Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, The Waterfront Journals, and Memories That Smell Like Gasoline. His artwork has been included in solo and group exhibitions around the world, at institutions such as The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The American Center, Paris, France; the Busan Museum of Modern Art, Busan, Korea; Centro Galego de Arte Contemporanea, Santiago de Compostela, Spain; Barbican Art Gallery, London, UK; and the Museum Ludwig, Cologne Germany, and is in the permanent collections of The Whitney Museum, New York; Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Japan; and The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among many others. In 2010, a re-edited excerpt of Wojnarowicz's film A Fire In My Belly was removed from the exhibition HIDE/SEEK, hosted by the Smithsonian Institution's National Portrait Gallery, igniting a strong debate around the censorship of art. In his lifetime, Wojnarowicz had won a precedent-setting Supreme Court case against Donald Wildmon and the American Family Association when it misrepresented his art in a campaign to protest NEA funding allocations.