Description

From behind a pyramid of TV monitors, perhaps calling to mind the TVs stacked for destruction in Ant Farm’s Media Burn (1975), Jenkins slowly rises, garbed in protective eye goggles and an American flag scarf. He begins to intone a haunting refrain: “You’re just a mass of images you’ve gotten to know, from years and years of TV shows…,” echoing the agitprop of the 1970s guerrilla television movement, which sought to tune people into their manipulation by commercial television. However, Jenkins trains his focus on mass media’s racial oppression. Intercut with his direct-camera performance, which grows increasingly more menacing and confrontational, Jenkins displays images from a long history of degrading Black stereotypes in mainstream entertainment, including vaudeville minstrel characters, exploited actresses such as Hattie McDaniel, and the sinister white supremacist propaganda of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation

(1915). By referencing vaudeville and early cinema, Jenkins emphasizes television’s capacity to broadcast and inculcate these racist images, collected through the centuries.

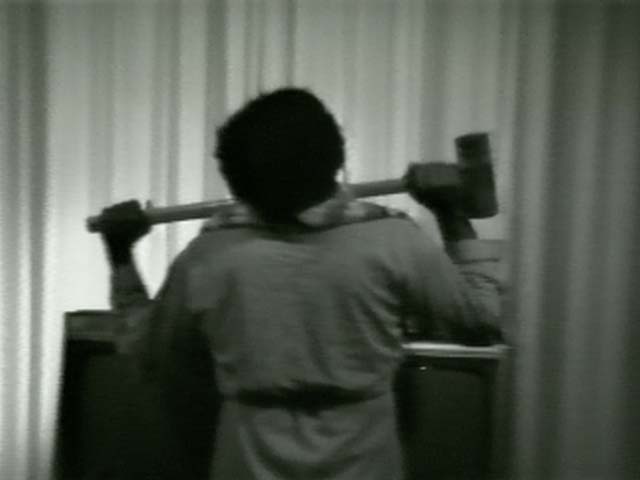

Jenkins rolls out from behind the monitors in a wheelchair, wielding a sledgehammer—an indelible image of seething, hobbled anger (accompanying Jenkins’s American flag scarf, this image resonates with then contemporary TV images of Vietnam veterans). Jenkins is hellbent on destroying the TVs but declares that he can’t because “they won’t let me.” Unlike Media Burn, which ends with a car ramming through its TV pile in a fiery burst, Mass of Images acknowledges that there are unseen forces preventing this cathartic destruction: namely, the racist ideologies permeating American identity. In the final instants of his performance, Jenkins turns his sledgehammer on the viewer, implicating each of us who has been indoctrinated by our years of television viewing.